About

Author: Mario Vargas Lhosa (Peru)

Genre: Historical Fiction

Setting

Place: Bahia, Brazil

Time: 1890s

My Rating (see what this means)

My Subjective Rating: 4

My ‘Objective’ Rating: 4.04

Introduction

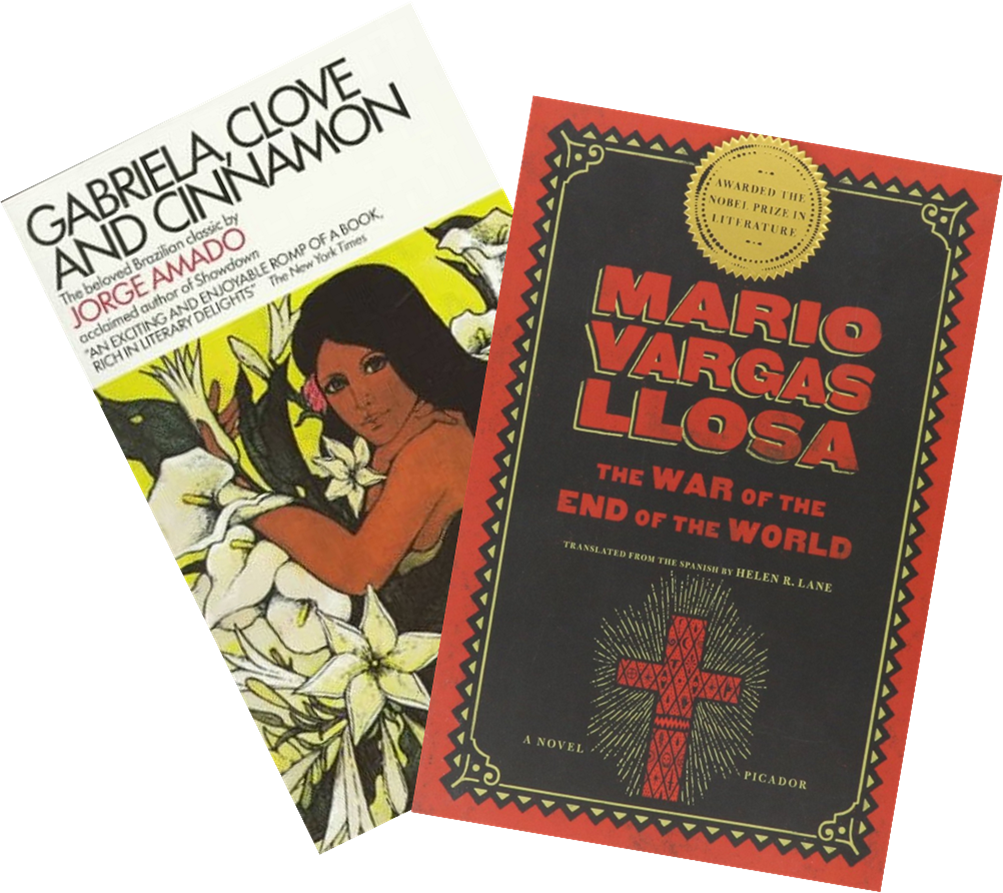

Several months ago, I was reading about Bahia, Brazil in the early 1900s – the mood was upbeat – the sure scent of progress was in the air and the forces of Coronelismo were crumbling. Sure, there were tons of miserable migrants coming in from the hinterlands – but they had endless opportunities along the coast. The book was ‘Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon’ by Jorge Amado and the town was Ilhéus in littoral Bahia.

The War of the End of the World also takes place in Bahia, around the same time, but the air is choked with desperation, droughts and dacoits. Corenelismo is still being challenged – not by progress and science however, but by rebellion and superstition. We dive into the lives of the miserable peasants who didn’t migrate to Ilhéus – and who became victims to the deadliest Civil war in the history of Brazil.

Synopsis

“[He is] even daring to tell the Republic: ‘hold on! You shall not pass…” (Newpaper caricature from the times)

The War of the End of the World is fictionalized history – centered around a few real world characters – notably the Counselor, a religious leader who rejected the new Republicanism of Brazil and created an independent citadel of Canudos. The counselor and his followers (jaguncos) – a ragtag band, even defeated one of Brazil’s most celebrated colonel – Moreira Cesar.

It is a novel about fanaticisms – the counselor’s (Religion) vs. Moreira Cesar’s (Republicanism) which upended the lives of thousands. Smaller fanatics – Galileo Gall, a Scotsman obsessed with revolution, and Rufino – a villager obsessed with honor, meanwhile were caught in their own battles.

Detailed Summary:

The overall narrative arc can be visualized as 3 key tragedies varying only in scale:

1. The National Tragedy: The Republic of Brazil vs. The Idea of Canudos

Towards the end of the 19th century, a New Brazil was emerging – Monarchy was overthrown and a progressive Republic declared. However, the only real manifestation of progress to be felt in the hinterlands – the abolition of slavery – was technically done by the king. The only other change that came with the establishment of the republic was ‘an increase in taxes’.

The counselor mistakenly believed that the Republic planned to reinstate slavery. He started to equate it with the ‘Anti-Christ’ and came to stand against everything the republic stood for – separation of church and state, civil marriages, taxes etc. The press started classifying him as a ‘monarchist’. However, this classification was tenuous at best. This failure of the politicians of Brazil to understand this drove them to a civil war against the very people the republic wished to empower.

The Cast:

The Counselor – Antonio Conselheiro was a demagogue. The key sources of his authority were his very strongly held, albeit stupid beliefs, great charisma and a selfless character. Perhaps someone like the counselor was inevitable in the misery of the hinterlands – and while he was the main driver of the events of Canudos; in the book, he remains mostly a mystical background presence.

The Politicians and the Army: The Bahia politicians, on the other hand – Canabrava, the leader of the monarchists & Goncalves, the leader of the Republicans, were both what politicians everywhere are – power-hungry, Machiavellian and driven by self-preservation. But the conflict with Canudos was soon taken over by the Brazilian army – manifested in the first half of the war by Colonel Moreira Cesar – a celebrated general, who seemed as convinced of the Republican ideals as the counselor was of his religious ones. The conflict inevitably was bloody.

2. The Local Tragedy: The Idea of Canudos vs. its People

Canudos was filled with a wide array of individuals who were there for reasons personal, societal or spiritual. This included –

- Brutal dacoits (Pajeu, Abbot Joao, Big Joao) who had turned a new leaf,

- Vulnerable misfits (Lion of Natuba, Little Blessed One, Maria Quadrado),

- Tired entepreneurs (Villanovas)

- Rebellious priests (Father Joaquim)

- Countless others with nowhere else to go

While Canudos provided them relief against the uncertainty around them, the underlying philosophy of Canudos was always fatalistic. The army just became the conduit of the destruction that the idea of Canudos long philosophized.

[Spoilers] The final tragedy unfolds as the war is ending, and devastation reigns Canudos. The little blessed one, without consulting the others, negotiates the surrender for the survivors. But the defenders of Canudos, end up shooting their own citizens to ‘save them the ignominy of dishonor’ that the surrender would have represented.

“Do you want to know what happened to Abbot João?” her toothless mouth stammers.

“Yes, I do.” Colonel Macedo nods. “Did you see him die?”

The little old woman shakes her head and clacks her tongue, as though sucking on something.

“He got away, then?”

The little old woman shakes her head again, encircled by the eyes of the women prisoners.

“Archangels took him up to heaven,” she says, clacking her tongue. “I saw them.”

3. The Personal Tragedy: The Self-nominated Voice of the Proletariat vs. The Proletariat

Galileo Gall had grand notions about his responsibility towards the world. A constant rebel with communist sympathies – he was a big supporter of Canudos – despite all the contradictions between the Counselor’s beliefs and his own.

His grand dreams however, were overtaken by a more earthly conflict with Rufino – whose wife, this celibate, ends up raping. Rufino becomes obsessed with revenge – not for Jurema’s sake, but for the sake of his honor. And Galileo ends up despising the very proletariat he wished to empower.

“I’m not your enemy, your enemies are the men who are blowing those bugles. Can’t you hear them? That’s more important than my semen, than your wife’s cunt, where you’ve placed your honor, like a stupid bourgeois.” …

For Discussion

Feel free to share your thoughts in comments

Was the tradegy of Canudos avoidable?

In the first chapter of Gabriella, Clove and Cinnamon, 2 ambitious young men, with the blessings of a progressive politician, had just started a transportation company – which would have reduced the travel time from coastal Ilhéus – to the nearest hinterland town by half. Progress would have taken the same bus.

In time, progress would also have reach Canudos. Famines would have become less frequent. People’s tolerance for demagoguery would have reduced. Perhaps Canudos would well have collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions much sooner. However, even without war – famines and droughts would have continued to kill for several years. Brazil’s initial coffee-presidents would hardly have prioritized ‘non-coffee’ interests.

Is devastation by war more tragic than that from forces of nature? If yes, then patience certainly would have prevented the tragedy of Canudos, in a sense of speaking at least.

Picture Credits:

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_of_Canudos

2. https://tiradentes-geographie.com/2020/11/30/the-canudos-war-part-of-the-brazilian-national-novel-or-premise-for-institutional-violence/